Anna Greidanus recently found her passion for art and teaching intersect with an atypical locale: a remote village in northern Thailand.

Greidanus, a professor of art at Calvin College, spent two weeks this past summer with the Akha tribe of Thailand in Huisan village, teaching art classes to native children. The Akha people live in the hills of six different Asian countries. Even after long days in school, the Akha children approached Greidanus with an eagerness to learn.

“They would go to school during the day, and then to my amazement, after a full day of work in school, run up the hill as fast as they could to take art lessons with me,” Greidanus said.

The children living in the village do not have many of the technological gadgets used in the West. As a result, Greidanus said the children approached the art lessons with single-mindedness.

“I found that the students—even the youngest ones—were amazingly focused,” she said. “They don’t have computers, they don’t have screens. Likely they don’t have televisions. These children could really focus on art making, and they did.”

More important than a lack of technology, the Akha children in Huisan are not born with citizenship, and although they can take a citizenship test as a teenager, very few are able to pass because of a lack of literacy and knowledge about Thai culture. Those who fail the citizenship test are marginalized and do not have the basic rights of a Thai citizen.

Greidanus views art education as a vehicle for enabling cultural rootedness and affirming personal and communal identity, especially during times of tremendous transformation, which is currently occurring within the hill tribes of northern Thailand.

Partnering with AYDC

Greidanus worked with the Akha Youth Development Center (AYDC) in order to help children in the region receive a better education so that they can become fully integrated citizens of Thailand. The AYDC is led by Luka Chermui, who is also an Akha tribesman. Chermui was in line to become one of the tribal shamans (a leader who connects with the spirit world), but changed course after his parents converted to Christianity. “His parents were some of the very first Christians in the entire Akha tribe,” Greidanus explained. “Quite an amazing story.”

Because of Chermui’s native Akha heritage, the AYDC is able to help the children in the region develop skills in language and education while also maintaining their cultural customs and heritage.

“What is really exciting about this particular organization is that they are deeply Christian, and the education offered is based on the vision and roots of the Akha people themselves,” Greidanus said. “So it’s not about trying to repress the culture of these children, but [rather, to] allow them to embrace their own culture and their own cultural roots, and at the same time gain the education they need to be fully functioning members of Thai society, and less vulnerable to the problems that marginalized people have in that culture, which include drug and human trafficking.”

Teaching without barriers

Living near the community center building—the nucleus of the AYDC campus—for two weeks, Greidanus taught art classes to the impoverished children in the village. “What I did was basically lead an art workshop for these kids,” she said.

Although Greidanus did not speak Akha, and the Akha children did not speak English, she was able to engage and communicate with the children via art.

“The wonderful thing about the experience was language was not a significant barrier,” she said. “I literally spoke English the whole time, explaining things, they were watching me, and listening, listening and seeing with their eyes.”

Art as a shared language

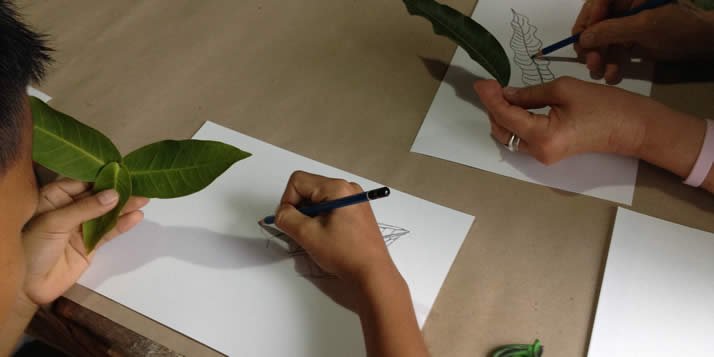

She used tangible objects from nature that the children would be familiar with.

“I started by asking them to draw trees, and demonstrated art-making techniques, [so] they could draw from their imagination,” she said. “They added creatures to the trees—birds, insects and whatever they decided to do. As that progressed, we moved into observational drawing from the world around them, so I brought in leaves, vegetables, real objects.

“So the entire time I’m teaching a visual language, and they are understanding it. Through drawing, painting and working with visuals. I was able to give them art supplies, show them techniques, and work with them. They eagerly got involved.”

During the two weeks, the children transformed the community center into an art gallery proudly displaying their work.

“It was exciting, to not only do a limited workshop, but in that context, be able to produce enough work with these kids to create an art show, a gallery, where the entire community is invited to look at the work,” Greidanus said. “[The art] was up on Sunday when we had a worship service there, and the kids were pointing excitedly at their work, and that was really great.”