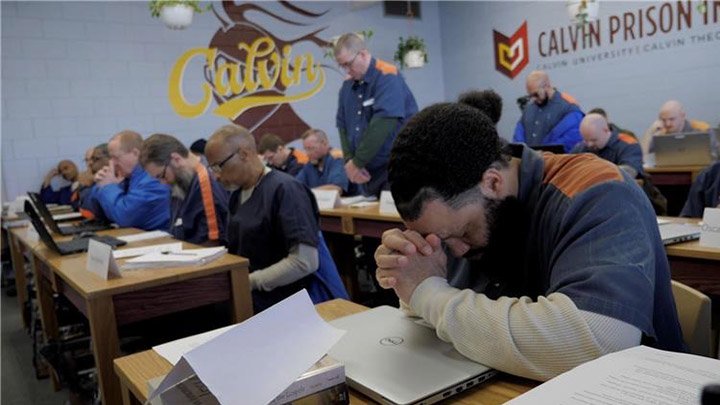

Every morning, inmates like Rick at the Handlon Correctional Facility in Ionia, Mich., are reminded of “what” they are.

A number. Six digits span the upper back of their dark blue uniforms.

Captives. They are confined most of the day to 6x8 foot cells secured by metal bars.

Dangerous. Guards stand watch of every move. And a 20-foot-tall barbed-wire fence ensures they know there is no escape.

And these are just the visual reminders.

“We all live in a world where the burden of proof is upon us that we are worthy of being loved. If that’s true in society generally, that’s true squared in an incarcerated setting,” said Dale Cooper, chaplain emeritus of Calvin University. “Day after day after day, they are reminded that they are chunks of protoplasm. The thing that defines them is ‘you’re an inmate.’”

Re-forming an identity

For pastors like Cooper and Lisa DeYoung, that definition isn’t right.

“We understand the importance and the opportunity of reminding these men that the image of God in them is what qualifies, not less than everything,” said Cooper.

Cooper and DeYoung are building upon the work of the Calvin Prison Initiative program, which for the past seven years has been equipping inmates to be Christ’s agents of renewal, offering 20 students each year the opportunity to pursue a bachelor’s degree from Calvin University behind bars.

While the CPI program is training up leaders to be Christ’s agents of renewal inside prison walls, there are some who feel a specific tug toward pastoral ministry. In 2019, the Jubilee Fellows Program, a program that’s operated on Calvin’s main campus since 2002, was expanded to the Handlon campus. The program helps students who are inclined toward Christian leadership and church ministry to discern their calling.

Confirming a calling

While some students aspire to become preachers in one of the 31 Michigan Department of Correctional Facilities, with some already doing this work at Handlon, there are many other needs to fill as well.

“Pastoral care for fellow inmates, that’s a big important thing,” said Cooper. “We’ve talked about serving as a pastor amid grief, serving as a pastor when fellow inmates are dying—which is a hugely neglected area—proclaiming the good news, and training them in evangel-living.”

On their mid-term evaluations this fall, students in the class reflected on their experience thus far. What those evaluations showed is that it’s clear the two main goals of the course were being met: to foster and encourage (Christian) community among Jubilee Fellows members, and secondly to educate regarding the life, goals, and calling/work of a pastor, and to encourage the fellows to consider whether this calling might be for them.

“Your preaching—with and without words—has been a beacon of trust, humility, and learning. You have seamlessly brought together and cultivated men from various backgrounds, religious preferences, and education,” wrote Rick, of Cooper and DeYoung, “and you have done so with quality humanness and divine Godliness.”

“Everyone is both student and teacher,” wrote David. “This is more than just a class, it’s ministry.”

“Rick’s told me continually ‘what I have come to discover through CPI and more specifically Jubilee Fellows is my worthwhileness as a human being, and that my insights are valued,” said Cooper.

Supported by community

Nicholas Wolterstorff, an emeritus professor of philosophy at Calvin, was struck by how true this was during a recent visit to Cooper and DeYoung’s class. He asked the class: “The message you get is that you’re not worth much. So here is my question for you: How do you manage to maintain a sense of dignity in such a situation?”

In a written reflection afterwards, he wrote: “I was moved by the response I got. Some eight to ten men spoke up. And what they all said was that it was their participation in the Calvin Prison Initiative that had given them a sense of self-worth, a sense of dignity. All their Calvin teachers treated them with dignity and helped them believe they could do the work. They were now different persons from the persons they had been before they enrolled.”

Rick’s six-digit number on his back is hardly visible, it’s literally faded over the years. And so has the definition that number carried with it. He’s no longer a “what,” he’s a “who” – and he’s reclaimed so much more than that interrogative pronoun.

Remembering one’s value

“If you want to preach to inmates, just remind them that they are of value in the sight of God,” said Cooper. “Several years ago one of my students [an inmate] asked me ‘Pastor Cooper, do you look upon me more as an inmate who happens to be a student or as a student who happens to be an inmate?’ I could say to him, I look upon you, with me, as one who is understood, accepted, loved, treasured, and valued by the God who pulls us together.”

That’s what men like Rick hope to convey to their fellow inmates now.

“I learned to grow into a young man who deserves to be seen as human. Before Calvin, I was simply a scarred (and scared) little boy fearful of life,” wrote Rick. “After Calvin (as if there is ever an “after” Calvin) I am a man who seeks to bring hope to others who live in the strongholds (caves) that I once resided in.

“The days I share with our class inspire, uplift, and direct my life. As John the Baptist leapt in the womb, so my Spirit leaps on these days. I crave a community such as this on a more daily basis.”

It’s up to men like Rick, through the powerful work of the Holy Spirit, to make this true of their square inch.