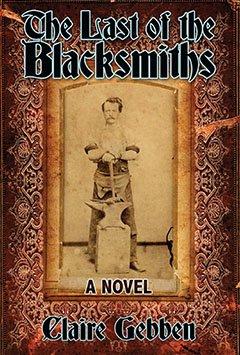

The Last of the Blacksmiths by Claire Patterson Gebben ’80, Seattle, Wash.: Coffeetown Press, 2014, 318 pp., $16.95.

When Claire Gebben first started learning about her German ancestors, their world seemed far removed from her modern life. But she soon realized, “the veil of history gets very thin.”

“One hundred and fifty years now seems short,” she said. “I started to see relationships and personalities born again throughout my family. I felt like I knew the people I wrote about somehow.”

Part of Gebben’s personal relationship with the characters comes from learning about them in their own voices: The Last of the Blacksmiths was inspired by a discovery of old letters Gebben’s father had tucked away in his belongings, dating back to the 1920s.

Gebben’s paternal grandmother had kept up a correspondence with descendants from her grandfather’s brother, who had never emigrated from Germany. The letters were written in Alte Deutsche Schrift, a flowery text used in the late 1800s and early 1900s.

Gebben, who didn’t speak German nor have the ability to read the text, sent the letters to her relatives, thinking they might like to have them. What Gebben wasn’t expecting was a return package—hand-delivered—of a dozen letters dating back to 1860, written mostly by Michael Harm, Gebben’s great-great-grandfather.

In puzzling over the now-translated letters, Gebben began to learn much about her family’s immigration to America as well as the history of the times.

The result, The Last of the Blacksmiths, is a work of historical fiction, based on the story of Harm’s immigration and life in America in the late 1800s and early 1900s.

Harm came as a youngster to America in 1857 from Freinsheim, Germany, to apprentice as a blacksmith with his uncle, who had settled in Cleveland, Ohio. The work was grueling, but Harm managed to fulfill his duty, become a journeyman, a wagon maker and eventually a master carriage builder.

Gebben writes in detail about the work as she was able to experience it firsthand while taking a blacksmithing class in Washington state, where she now lives.

“When I started the research I thought blacksmiths shoed horses,” she said. “I pictured my ancestors shoeing horses in a barn.”

Gebben was surprised to discover the craftsmanship involved in blacksmithing when she took a class from a master blacksmith, learning to craft tools, fireplace pokers and a sign bracket.

In addition to blacksmithing skills, Gebben also learned much about American history and the German influence on it. “People don’t know what a key role Germans played in the 19th century,” she said. “Many of them were political revolutionaries. They were very concerned about keeping their freedom and disagreed strongly with slavery; they were very much pro-Lincoln and were influential in getting him elected.”

Much of this history remains unrecognized because of anti-German sentiment following World War I and World War II. “People stopped talking about their heritage,” said Gebben. “It was a very bad thing to be a German, so people whisked it under the rug.”

Beyond a history of her family and even German immigrants, Gebbens tells a universal story of change.

“I read a book in my research called What Hath God Wrought. The subtitle is The Transformation of America 1815-1848. When I saw that I thought, ‘That can’t be right, dramatic change in the early 1800s?’ Once I read the book it gripped me as a theme. All of the inventions that were occurring in Michael Harm’s lifetime, from the use of wood to whale oil to petroleum and kerosene. And transportation from canals to railroads. And telephones.”

When the book ends, Harm’s livelihood of blacksmithing and finally, carriage making, has all but been eclipsed by the invention of the automobile.

“I wanted the book to be nonfiction but then I wouldn’t have been able to include people’s emotions,” she said. “And I thought it was important to give a voice to someone who had experienced so much change in their lifetime. I felt like the story was more about everyman.”