By Mike Van Denend '78

Paul Vanden Bout '61 stands beneath the Green Bank Telescope, the world's

largest steerable radio telescope.

How would you spend your last day at the office? Maybe you’d be glad-handing colleagues, packing away the family pictures, cleaning out computer files, attending a going away luncheon.

It’s Paul Vanden Bout’s last day as Director of the National Radio Astronomy Observatory (NRAO) on the University of Virginia campus, and he’s driving a truck winding along U.S. 250 through the Shenandoah Mountains on his way to the tiny hamlet of Green Bank, W.V.

Since 1985, Vanden Bout has led the NRAO to the forefront of astronomical research, with Observatory telescopes making nearly as many scientific discoveries per year as NASA’s Hubble telescope. He’s leaving his director’s post, but not to relax in a hammock behind his peaceful Charlottesville home. Instead, he will be interim director of the NRAO’s next and most ambitious endeavor, “ALMA” (Atacama Large Millimeter Array), an array of 64 radio-telescope antennas that will explore the universe from mountainous heights in the Atacama Desert of Chile.

But for now, the 1961 Calvin graduate is content to take in the beautiful hills and valleys on the road to Green Bank. I’m grateful to be along for the ride.

We’re on our way to the Robert C. Byrd Green Bank Telescope (GBT), the world’s largest steerable radio telescope. Vanden Bout, as NRAO director, has been responsible for the Green Bank site, as well as the VLA (Very Large Array), a 27-antenna system near Socorro, N.M., and the VBLA (Very Large Baseline Array), a widely-scattered system of antennas across North America, with Mauna Kea, Hawaii, on one end and St. Croix, Virgin Islands, on the other. Vanden Bout plans to add the ALMA site in Chile to this impressive collection of radio astronomy telescopes.

As we head into another picturesque town on the western edge of Virginia, Vanden Bout tries to explain radio astronomy to me. The field is the lesser-known relative of visual astronomy, the version most people recognize and was brought back into the limelight with the Hubble.

“It is a bit humorous to note that most radio astronomers don’t know their way around the night sky well,” Vanden Bout says. “I’m taking a group of young people from my church to Ghost Ranch in New Mexico and those clear skies will be full of stars. I’ll have to bone up on my stars, because the kids will expect that of me.”

Radio astronomers steer telescopes to the point in the sky they’re working on and use radio waves to see things in the universe impossible to observe by the eye or any visual telescope. That’s because visible light consists of only a small part of the range of existing electromagnetic waves; radio waves are at a much greater wavelength. It turns out that a number of celestial objects emit more strongly at radio wavelengths. Thus, since the radio astronomy field was first discovered in 1932, a host of new findings about the universe have been uncovered.

The first radio telescope was built by Grote Reber in his Wheaton, Ill., back yard. After World War II, radar technology gave the field a jump-start, which hasn’t abated since. More recently, the configuration of “arrays” —a series of computer-tied telescopes that can be aimed at the same target area—has helped scientists gain a much more complete and faster understanding of the workings of the universe. Before 1980, for example, researchers had to observe for days to get results; after the VLA, results were obtained in just hours.

“Use of the telescopes is free, but scientists must send the NRAO short proposals to explain intended use,” explains Vanden Bout. “There are three deadlines a year. We have referees from universities across the country read the requests and decide which researchers get scheduled for the various telescopes.”

Researchers who are approved prepare a detailed observing plan. NRAO staff members execute the observation and send the scientist data via the internet. Images can be constructed using special software. Thus, radio astronomers tend to be staring at computer screens rather than the constellations in the night sky.

Funding for the NRAO comes through the National Science Foundation (NSF) through Associated Universities, Inc., which manages NRAO’s activities.

The other misconception about radio astronomy, popularized by the 1996 Hollywood movie Contact, with Jodie Foster in the lead role, is that scientists hear things.

Paul Vanden Bout overlooks the nearly two-acre surface area of the Green

Bank telescope which has helped "delve into the origin of galaxies."

“I guess the word radio throws people off,” surmises Vanden Bout. “Radio telescopes are designed to make images of things in the universe, and different wavelengths produce different images. We’re simply adding different information to what visible astronomy has given us. The Milky Way, for example, is not just stars—there’s gas and dust particles and clouds of molecules. We’ve even been able to delve into the origin of galaxies.”

Some of the scenes in Contact were shot at the VLA in New Mexico, Vanden Bout says, but “while entertaining, the movie doesn’t explain real radio astronomy.

“One thing we never do,” he asserts, “is put on headphones.”

At last we roll into Green Bank in West Virginia’s Pocohontas County and the enormity of the GBT becomes evident. It towers over the countryside—understandable since it is taller the Statue of Liberty, weighs 16 million pounds and boasts nearly two acres of surface area.

The GBT wound up in this out-of-the-way place for two reasons—the telescope’s lead advocate Senator Robert C. Byrd of West Virginia and the location, smack dab in the middle of the National Radio Quiet Zone, a 100-mile section of Virginia and West Virginia established in 1958 by the FCC to minimize interference with the radio astronomy going on in Green Bank. Most travelers note troubles with cell phones in this region of the country. There’s a good reason.

“Any application for a tower in the Quiet Zone gets scrutinized by the FCC and us,” notes Vanden Bout. “We calculate the effect on the telescopes and approve or deny based on that.”

Vanden Bout gets to have his “farewell luncheon” anyway, but it’s at the Green Bank cafeteria surrounded by a number of the 100 persons who work there. The staff of Green Bank is obviously thrilled that he decided to spend his last day at their workplace.

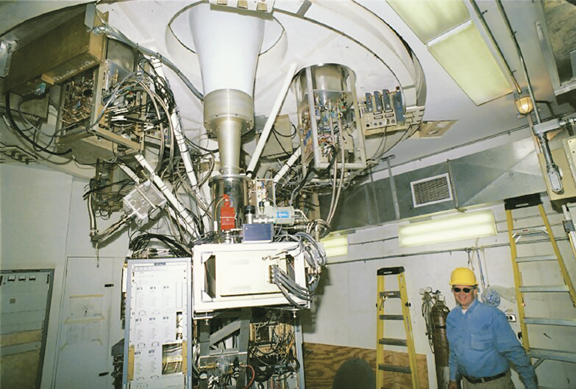

Inside the Green Bank Telescope

We take a tour of the amazing scientific facility and, while in the

control room for the GBT itself, note that two university researchers

are pointing the telescope at a particular galaxy looking for traces

of formaldehyde.

“Radio astronomy can detect molecules of all sorts, which help

us understand the make-up and origin of celestial bodies,” Vanden

Bout explains. The wide variety of radio astronomy being done, at many

frequencies, is helping to put more pieces in the universal puzzle.

And he’s contributed personally to that understanding. Ten years ago Vanden Bout and a colleague, Bob Brown, detected carbon monoxide in the interstellar gas of a distant galaxy. This object is so distant, it exists at an epoch when the universe had only 15 percent of its present age. The presence of CO is a sign that stars are forming. The possibility of studying star formation in early universe galaxies is part of the rationale for the ALMA project in Chile.

At last, we head for the GBT itself, driving in a grand old blue diesel Checker cab, the pride of the Green Bank staff. Once there, our host, Green Bank publicist Gregg Merithew, fortunately knows he must “lock-down” the telescope so an unwary technician doesn’t decide to steer the apparatus while the three of us are high above the ground near the GBT’s surface area.

Standing on a catwalk, many stories above the ground and taking in the immense size of this scientific marvel is an incredible experience. The GBT boasts a reflecting surface with the area of two-and-a-half football fields, connected to 2,200 motorized tractors that can adjust the shape of the dish to the researcher’s specifications.

“Parallel rays travel across the universe, then reflect off the GBT surface and come to a single point,” Vanden Bout explains. All three telescopes can observe roughly the same frequencies, but the different designs and alignments of the GBT, VLA and VBLA make one or the other better to use for specific research.

For Vanden Bout, his research into the galaxies fits hand-and-glove with his faith in an amazing Creator God.

“I know other scientists have had to grapple much more than I with the faith-and-science issue,” he said. “It’s always been a fairly straightforward thing for me. I don’t think the Bible is the source for ‘how’ questions; it addresses the ‘why’ questions. Since Galileo’s time, some have been worried that science will contradict the Bible. But if you don’t insist on the Bible being a science textbook, you shouldn’t have that conflict.”

The view from the top of the GBT is breathtaking. Yet this vista, seen by the naked eye, is incomprehensibly small compared to the vision offered by the telescope itself.

Vanden Bout’s next project, ALMA, will take the field one step further.

“When one wants to go higher in radio frequency, water vapor is a problem, so we need another radio astronomy center that is both clear and dry,” he explains. “The site in Chile is just that. It’s 16,500 feet high in the north Chilean desert. In some parts of this region it hasn’t rained in 400 years.”

It will be 2012 before ALMA is completed and that’s if everything goes according to plan. This is the challenge Vanden Bout takes on next, with an international team.

“The ALMA project is a $552 million joint effort of a partnership between the U.S. plus Canada and a European coalition,” he explains. “The Chilean government has been very cooperative and good hosts thus far.”

Vanden Bout is only working on the project through this year, making certain the international coalition interested in seeing ALMA happen hangs together. Then, it will a “traveling sabbatical” with wife Rachel (Eggebeen ’61), retracing their steps together through Paul’s early research career at Columbia University and the University of Texas in Austin, with a stop at the University of Chicago.

Rachel will be taking some time away from her volunteer work in Charlottesville for the Alliance for Interfaith Ministry and Play Partners, local social outreach agencies.

He’s met a number of Calvin alumni during his journey as a scientist and astronomer. Paul Zwier ‘50 was his Grand Rapids Christian chemistry teacher and large early influence; Vanden Bout also remembers being pulled toward the sciences at Calvin along with buddies Roger Brummel ’61 and Peter De Vos ‘61. After Calvin, he put off his enrollment at MIT in physics and took a Fulbright scholarship to the University of Heidelberg in Germany in mathematics. There he became acquainted with another Calvin grad, (now U.S. Congressman) Vern Ehlers ’56, who was in Germany on a NATO fellowship. Ehlers convinced Vanden Bout to go to UC-Berkeley instead, where the young researcher met up with yet another alum, Alex Dragt ‘58. Both Ehlers and Dragt have received the Distinguished Alumni Award from Calvin.

“And I’ve always been connected to what Calvin’s doing in astronomy,” says Vanden Bout. “Howard Van Till (’60) and I are great friends and colleagues and the two professors there now—Deborah Haarsma and Larry Molnar—are on NRAO advisory committees and use the telescopes.”

We come down from the GBT and travel back to the main Green Bank administration center, where a spacious visitor’s center is being constructed. Reber’s original Wheaton radio telescope is fixed nearby. After the center is completed, perhaps more people will soon take the winding roads to West Virginia and learn about the fascinating world—or should I say, “worlds”—of radio astronomy.

“Some people have a hard time with science because of the deep desire for fixed answers,” reflects Vanden Bout. “Many want to ‘learn and know.’ But science is really a way of thinking, of inquiry. We only ‘think so at this time.’ Some don’t want to live with that uncertainty.

“But for Christians, the most important answers are already known. We don’t need pat answers to the mysteries of the universe. We are free to be curious, explorers of planets, stars and galaxies far beyond our imagining.”

And with that, driving away from Green Bank with the sun setting over his shoulder, Paul Vanden Bout completes his 17-year tenure as Director of the National Radio Astronomy Observatory. He’s quiet on the way home, pleased with what he saw on his last look at Green Bank and looking forward to more Chilean adventures.

“Let’s see,” he says. “I have to pack for New Mexico and Chile—I’m going right from the youth group retreat at Ghost Ranch to a meeting with Chilean officials. I’m afraid I’ll have to take a suit.”

He pauses and smiles. “No guarantees how my suit coat will look

by then."

NSF Grant

$130 for two new telescopes—one at Calvin and one at Rehoboth

in New Mexico

Research by Calvin Profs

Deborah Haarsma and Larry Molnar are are taking Calvin’s study

of astronomy to new heights

Calvin's Observatory

Department of Physics & Astronomy

Calvin’s astronomy program reaches for the stars

Paul Vanden Bout isn’t the only radio astronomer with Calvin ties. In fact, two of them are teaching on the college campus.

Both Professors Deborah Haarsma and Larry Molnar are scientists with skills in radio astronomy and they’re taking Calvin’s study of astronomy to new heights.

“Last spring my collaborators and I made 30 hours of observations at the VLA in New Mexico and I was just at Green Bank for an NRAO meeting,” said Haarsma, an MIT graduate, who, along with the Harvard-trained Molnar, has presided over an increased emphasis on astronomical research at the college.

Since radio astronomy is still quite new, and emerging technology continually makes more research possible, the area is a growth field and Calvin students are following their professors in that direction.

“We’re giving students a good look at modern astronomy,” Haarsma said.

For years, Calvin provided astronomy courses mainly for non-science majors, but that’s changed as the physics department has upgraded facilities (including plans for new telescopes), added courses and approved an astronomy minor.

There are even summer research opportunities. Juniors Phil Ammar (Muscat, Oman) and Catherine Boersma (Surrey, B.C.) spent this past summer analyzing data from the NRAO’s Very Large Array telescope in Socorro, N.M., learning data analysis techniques and meeting students from all over the world.

“We’ve been searching for gravitational lenses,” explained Haarsma. “These lenses can be used to answer all sorts of questions about the universe, including how fast it is expanding and how galaxies have changed over time.”

She notes that, out of the 60 known gravitational lenses, over a third of them have been discovered through radio astronomy research.

“Radio astronomy is the boon industry,” she said. “New instruments have made the field more attractive to researchers.”

Haarsma and Molnar see the burgeoning interest at Calvin, too, with increasing enrollments in astronomy courses for science majors and more physics majors planning astronomy careers.

And what’s happening at Calvin is happening among other Christians interested in science. Haarsma maintains an e-mail list of Christian astronomers that has now grown to more than100 from all around the world.

“We’re building community, talking about astronomy and

faith,” she said. “There aren’t many astronomers out

there and fewer of them are Christians, so this lets us connect with

others who take both their faith and their science seriously.”