By Lee Hardy

President Woodrow Wilson once said that trying to revise a college curriculum is a lot like trying to move a graveyard. He did not expand upon that remark. But surely he had in mind the fact that both projects will encounter the resistance of the living as well as the inertia of the dead. He may also have been referring to the level of joy that invariably accompanies such tasks. He was, at any rate, in a position to know, for he had come to the Oval Office from Princeton University.

Lee Hardy is professor of philosophy and chair of the Core Revision

Committee

For the last few years Calvin College has been doing its fair share

of educational earthmoving. And it now has something to show for it.

Next year it will inaugurate its new core curriculum. Herein lies the

story.

In the fall of 1996 Calvin College created an ad hoc committee with a twofold mandate: to review and re-state the purpose of the core curriculum; and to review and revise the structure of the core curriculum. No small task. The college had tried twice before to revise the core curriculum, and failed both times—once in the late 1980s, once in the early 1990s.

Sobered by the lessons of recent history, the Core Revision Committee decided to tackle its mandate sequentially, and slowly. It devoted an entire year to crafting a new statement of purpose for the core curriculum. Entitled An Engagement with God’s World, that statement was approved unanimously by the Faculty Senate in the fall of 1997. The committee then turned its attention to the structure of the core curriculum. Its proposal for a revised curricular structure was passed in the spring of 1999. A package of new core courses was approved in the fall of 2000.

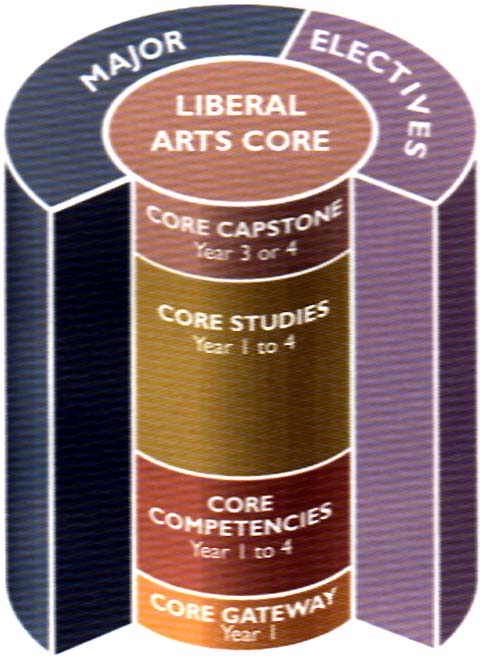

Layers within the Liberal Arts Core

Four years of hard work, close consultation, pointed debate and difficult compromises. Was it really necessary? Was the old core broken? In the late 1960s Calvin built a strong, expansive and thoughtfully designed core curriculum. Some 33 years later that curriculum was still operable. But over time it had demonstrated its share of shortcomings. Using the analogy of car repair, the revision of the old core was by no means a major overhaul. But neither was it a minor tune-up. It was something on the order of a valve job.

Here is a short list of ailments that brought the old core in for repair:

1) A lack of clarity about the purpose of the core curriculum. The expressed aim of the old core was to introduce Calvin students to the methods, results and approaches of the various academic disciplines. How the aim of the core was connected to the overall purpose of a Calvin education—preparing students for lives of Christian service in society—was not, however, spelled out in convincing detail. As time wore on, students took core courses simply because they had to; faculty members taught them largely as they wished.

2) Lack of oversight. Disciplinary majors and professional programs are owned, operated and defended by departments. The core curriculum, however, had no such home or guardian. Without an advocate on campus, the core was left to fend for itself and was often co-opted by departmental interests.

3) Fragmentation and complexity. By the late 1990s more than 260 courses in the Calvin catalog counted for core. With so many options for satisfying core requirements, the college had no way of ensuring a common body of learning.

4) Lack of sequencing. Due to fragmentation of the core, faculty members teaching upper level courses could assume very little by way of a common learning. Thus there could be little development of core themes at the different levels of the college curriculum.

5) Failure to communicate the Reformed vision to all students. CPOL (Christian Perspectives on Learning) was the integrative flagship of the old core. Originally it was to be taken by all students. But upon its implementation it was reduced to an option in the contextual disciplines. As a result, it captured only about half of the student body. In a core assessment pilot project of 1997, 33 sophomores were interviewed and asked if a Calvin education displayed any particular faith perspective or worldview. One third said they weren’t aware of any such thing.

6) Missing elements. In certain respects the old core had not kept up with the world—with the spectacular growth in media and information technology, with the cultural diversification of North American society, or with the process of globalization.

One of the striking features of the new core is its re-formulation of the purpose of the liberal arts core curriculum at Calvin. In the old regime, the purpose of the core was to introduce students to the methods, results and approaches of the various academic disciplines. The new core envisions the academic disciplines not as the objects of core education, but as the means of core education. As a liberal arts institution, Calvin seeks to prepare students for lives of Christian service in a wide array of domains. No matter what profession students might pursue after graduation, they will also be citizens, parishioners, players in a market economy, participants in the culture and members of a society deeply shaped by science and technology. The new core asks the disciplines to provide students with the insights and skills they will need to be informed and effective agents within these domains of practical life. Core courses should be taught not as if they were the first course students take in a major, but as the last course they take before they find their place in the world beyond Calvin’s campus.

With this conceptual move the new core at Calvin connects to a very old tradition. Liberal arts education had its beginning in ancient Athens. It was designed for those destined to participate in the political life of their community. That is, it was designed for those who were free from the necessity of work and thus free to engage in the affairs of state (hence the word "liberal"). The first order of study in the old liberal arts curriculum was contained in the "trivium" –grammar, rhetoric and dialectic. Grammar was not simply the study of the mechanics of a language. Rather it involved sustained exposure to the canonical texts of particular culture, texts by which that culture’s ideals and values were envisioned and commended. The study of grammar was to shape and form students, to show what a good life is like, how a good person should live. Rhetoric was the chief means of persuasion, and hence the key to power in Athenian democracy. Rhetoric was designed to make students effective agents in society. Dialectic was a training in the construction and assessment of knowledge claims. In short, classical liberal arts education was to make people virtuous, effective and intelligent.

The new core at Calvin carries all three of these traditional elements into the project of Christian liberal arts education. It is divided into three components: knowledge, skills and virtues. There are things about God, the world and ourselves that we want all Calvin students to know; there are skills we want to impart and enhance; and there are certain traits of character we want to foster in the classroom and in the community at large. Each of these three components is shaped by the aim of preparing students for lives of Christian service in contemporary society. Such is the purpose of the new core.

Back to the list of repairs. To address the lack of oversight, the Core Revision Committee recommended the formation of a standing Core Curriculum Committee. This committee, composed of faculty, administrators and students, is mandated to oversee the development and assessment of the entire core curriculum.

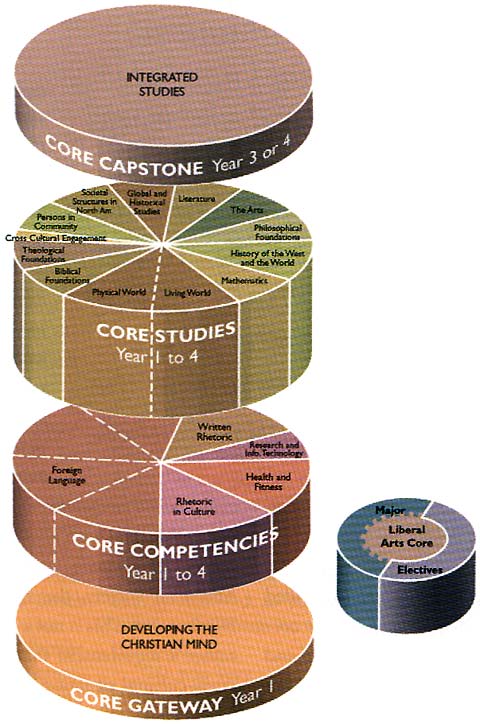

Pieces within the Liberal Arts Core

To address the problem of fragmentation, the revision committee took several measures. One was to require all students to take a first-year interim course designed to introduce Calvin’s tradition and mission. Like CPOL, this course seeks to acquaint students with the Reformed worldview. Unlike CPOL, this course will have different versions, depending upon the instructor’s areas of expertise and interest. All students will read a monograph written by Dean of the Chapel Neal Plantinga that sketches out in broad and compelling strokes the holistic interpretation of the central Christian doctrines of creation, fall, redemption and restoration. With their instructor, students will explore how this worldview applies to contemporary issues in, say, bio-technology, the environment, the media or the political arena. Thus they will get an early and vivid introduction to Calvin’s central intellectual project: the articulation of a Christian worldview and a faithful engagement with the ambient culture. These themes are re-visited, at the other end of the core, in upper-level integrative studies courses, which form a kind of bookend to the entire core education. Beyond requiring a common course, another measure taken to minimize fragmentation was to gather many core courses under trans-disciplinary categories, where each category has a set of objectives to be met all courses listed in that category. The total list of core courses has been reduced by 25 percent; but the main work of de-fragmentation is performed by common objectives within any category of core courses.

Finally, to catch up with the world, the Core Revision Committee has added a few elements to the new core. One is a one-hour course in information technology. This course, to be taken in the first year, is designed to bring all students up to certain level of computer competency. It also addresses ethical questions that arise in connection with the capabilities of information technology. To address the process of globalization, courses dealing with non-western regions of the world now have core status. To prepare students for the cultural diversity in North American society, the new core has a cross-cultural engagement requirement. This is not a new course, or even category of courses, but rather a requirement that all Calvin students spend some time in a cross-cultural situation. They may fulfill this requirement is a variety of ways—an off-campus interim, an off-campus semester program or through local involvement in service learning projects. The new core has also created a category of courses entitled "Rhetoric in Culture" which embraces course in both oral and visual rhetoric. Much of the communication in our society takes place by way of images. This category makes room in the core for the study of the rhetoric of the image.

There is one other feature of the new core that bears mention. This year, for the first time in its history, the percentage of incoming students from a CRC background dipped below 50 percent-- another way in which the world has changed, demanding a response from the college. Between the initial orientation at the beginning of the fall semester and the first-year interim course, all students will participate in a "Prelude" program. This program, a cooperative venture of the student life division and the academic division, provides a progressive orientation to the culture and demands of Calvin as a Reformed Christian academic community. Wellness and self-management, vocation, responsible freedom and cultural discernment are among the issues that will be addressed in the Prelude program.

In these and other ways the college is attempting to embody an education

that is academically rigorous, culturally relevant, deeply Christian

and thoroughly Reformed.