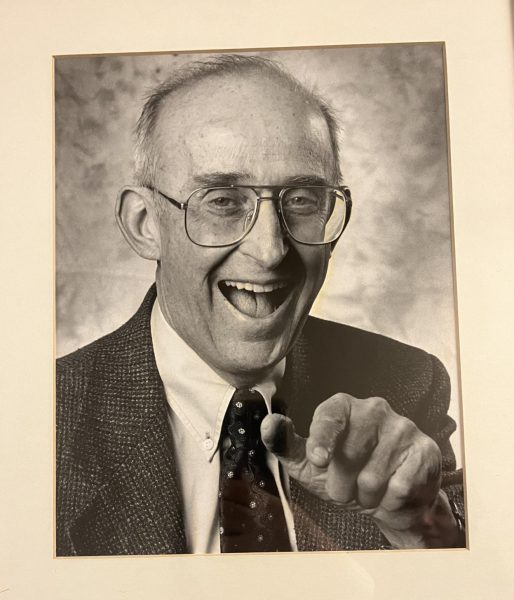

Stanley Hauerwas speaks at Wycliffe College on how to write theology

Last week, Anglican theologian Stanley Hauerwas traveled to Toronto to give a lecture at Wycliffe College. Hauerwas, a prominent theologian at the Duke Divinity School is the Gilbert T. Rowe professor of theological ethics. Often known for his strong stance on pacifism and his ideas of church-state relations, Hauerwas was even named “America’s Best Theologian” by Time Magazine in 2001. However, Hauerwas made it a point to note that “best is not a theological category.”

At Wycliffe College, Hauerwas spoke on the issue of how to write theology. Hauerwas made a case to bolster theology by maintaining close attention to the meaning of grammatical sentences. For Hauerwas, contemporary theologians “often confuse writing about theology with writing theology” and should attend to the ways to “write a theological sentence that has the potential to make a reader stop and rethink how they ought to think.”

Hauerwas’ discussion primarily concerned theology in the academic world and the way it has declined over the years in universities. But the issue of academic theology’s credibility is of no worry for Hauerwas, who said, “Theologians now have nothing to lose, so we can do our work with the freedom that comes to those who have nothing to lose. … We can write without apology — at the very least, that means we do not have to try to make what we believe acceptable to those who have decided that what we believe cannot be true.”

As reported by the Anglican Journal, Hauerwas argued that theologians sometimes have tried too hard to show that theology belongs in the academy alongside fields like philosophy. From this, theologians often confine themselves to writing theology according to the accepted norms of academic disciplines. Rather than writing on what others have said about theology, Hauerwas urged students and professors to refocus the discipline of theology on God. The important reminder for all Christians then, is that theology does not primarily consist of “writing about what theologians may or may not have said about God, rather than writing about God.”

This entails a return to the basics of writing good sentences. A good theological sentence must always keep in mind its limitations. Hauerwas argued that since God is not an abstract idea to be grasped, theological sentences cannot be intended to present a whole and absolute truth of God. Instead, theologians should aim to write sentences to express the truths that God has revealed by his relation to the world.

As an example of an effective theological sentence, Hauerwas quoted from theologian Robert Jensen: “God is whoever raised Jesus from the dead, having before raised Israel from Egypt.” Honing in on Jensen’s use of “whoever,” Hauerwas pointed out that it conveys a sense of relationality with God. “Whoever” does not convey a sense that God is wholly understood, but “resists the commonplace assumption that when someone says ‘God’ they know what they are talking about.”

Hauerwas also asserted the use of “whoever” in this sentence implies the necessity of the church. “Because the God who can be known only as the God who raised Jesus from the dead, having before raised Israel from Egypt, is known only through witnesses.” It is then the church’s duty to develop the ability of Christian believers to read these theological sentences and ascertain the theological truths revealed through grammatical structures and forms.

Hauerwas concluded that theology cannot be relegated to the confines of academia, but it must be the purpose to reveal God’s truth to God’s people. This requires good theological writing and good theological sentences: “Good sentences, and our ability to read them, do not drop from the sky. Rather, they are the result of a lifetime of training necessary to produce a soul capable of seeing through the sentimentalities we use to hide our mortality.”