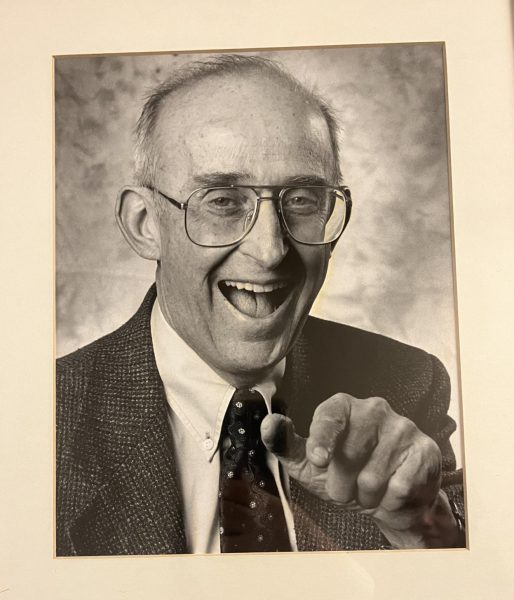

Gregory A. Smith offers a new interpretation of Platonic dualism

On September 30th, last Wednesday, the Calvin classics and philosophy departments hosted Gregory A. Smith for a lecture on substance dualism. Smith, a professor of history from Central Michigan University, offered to shed new light on Descartes’s argument for the mind-body duality.

There are many different types of mind-body dualisms in the philosophy of mind, and one of the most well known forms of dualism is Cartesian or substance dualism. Named after the French philosopher René Descartes, Cartesian dualism draws a sharp distinction between the body as material, and the mind as an immaterial and thinking thing. This concept of our minds or souls existing as immaterial, rational entities separate from our physical bodies is often taken for granted. However, much of this thinking should be attributed to Descartes who is often known best for the famous line “I think, therefore I am.”

Citing from Plato and Aristotle, to Apostle John and Paul, to Saint Augustine, Smith covered a wide perspective of historical thought on the relationship between the mind and body. Arguing that the model in antiquity for conceptions of the mind was predicated on a materialist view centered on the body, Smith emphasized that this understanding was accepted as the public consensus similarly to how Newton’s three laws of motion are assumed in the modern world.

In Greek the word pneuma is the same as the word spiritus in Latin, both are often used to convey “spirit.” In the Bible, pneuma is often associated with the Holy Spirit; hence the study of the Holy Spirit is pneumatology. However, Smith wanted to understand this “pneumatic” way of thinking as it was in antiquity. Rather than confining understandings of soul and spirit to a strict Christian correlation with the Holy Spirit, Smith suggested that pneumatic thinking was defined more broadly in terms of wind, air, and aether. For example, Paulinus of Nola, in an excerpt from the Carmina describes spirits with language that connotates breath, wind, and air. The Holy Spirit is similarly described in John 3:8 as a wind-like presence that “bloweth where it listeth.”

Smith argued that pneumatic characterizations in physical elements such as wind and air helped to suggest that ancient conceptions of immateriality were rooted on a material continuum. In this sense, immateriality is understood in a material sense. Using air as an example, Smith reasons that while it is invisible it is still material. Continuing to draw upon the imagery of invisibility, Smith illustrated that people in antiquity would have still conceptualized of invisibility as a material, possibly cloak-like, substance.

Smith also demonstrated the dominance of this pneumatic thinking by highlighting a number of texts from antiquity that conveyed this theme of material immaterialism. In Aristophanes’ comedy, Clouds, Socrates speaks of the mind as being made of the same “stuff” as the divine. Smith then pointed a few hundred years later to Cicero in his Tusculan Disputations for an explicit characterization of a pneumatic account of the soul and the cosmos. For Cicero, the soul and the cosmos are deeply interconnected in a material way. Finally, Smith looked to Apostle Paul for traces of pneumatic thinking in his first epistle to the Corinthians. Paul and his influence from Stoic philosophy similarly characterizes things with material “stuffs,” and uses this understanding in his explanation of resurrection bodies. Citing 1 Corinthians 15:39-49, Smith suggested that Paul may have been drawing a pneumatic connection between resurrection bodies and the celestial stars.