Background: Every year on the occasion of Hitler’s birthday (with the exception of 1934), Joseph Goebbels gave a radio speech in praise of Hitler. This is the second in the series, delivered in 1935. Goebbels, as usual, thought it a good speech. His diary entry for 19 April 1935 reads: “Dictated my speech for the Führer’s birthday. It went very well.”

The source: Adolf Hitler. Bilder aus dem Leben des Führers (Hamburg; Cigaretten Bilderdienst, 1936).

Fellow citizens! Two years ago on 20 April 1933,

only three months after Adolf Hitler came to power, I spoke to

the German people on the occasion of the Führer’s birthday.

It was not my goal then, nor is it now, to read out loud and passionate

newspaper article. That I shall leave to better stylists. Nor

will I praise Adolf Hitler’s historic work. I intend today, on

the Führer’s birthday, the very opposite. I believe it is

time to portray to the entire nation the man Hitler, with all

the magic of his personality, all the mysterious genius and irresistible

power of his personality. There is probably no one left on the

planet who does not know him as a statesman and as a remarkable

popular leader. Only a few, however, have the pleasure of seeing

him as a man each day from close up, to experience him, and as

I might add, to come as a result to a deeper understanding and

love for him. These few wonder how it is possible that a man

who only three years ago was opposed by half of the nation stands

today above any doubt and every criticism. Germany has found

a unity that will never be shaken. Adolf Hitler is the man of

fate who has the calling to save the nation from terrible internal

conflict and shameful foreign disgrace, to lead it to longed-for

freedom.

Fellow citizens! Two years ago on 20 April 1933,

only three months after Adolf Hitler came to power, I spoke to

the German people on the occasion of the Führer’s birthday.

It was not my goal then, nor is it now, to read out loud and passionate

newspaper article. That I shall leave to better stylists. Nor

will I praise Adolf Hitler’s historic work. I intend today, on

the Führer’s birthday, the very opposite. I believe it is

time to portray to the entire nation the man Hitler, with all

the magic of his personality, all the mysterious genius and irresistible

power of his personality. There is probably no one left on the

planet who does not know him as a statesman and as a remarkable

popular leader. Only a few, however, have the pleasure of seeing

him as a man each day from close up, to experience him, and as

I might add, to come as a result to a deeper understanding and

love for him. These few wonder how it is possible that a man

who only three years ago was opposed by half of the nation stands

today above any doubt and every criticism. Germany has found

a unity that will never be shaken. Adolf Hitler is the man of

fate who has the calling to save the nation from terrible internal

conflict and shameful foreign disgrace, to lead it to longed-for

freedom.

That one man has captured the hearts of the whole nation, despite the sometimes difficult and unpopular decisions he had to make, is perhaps the deepest, most amazing secret of our age. It cannot be explained only by his accomplishments, for it is just those who have had to make the heaviest sacrifices for him and for national reconstruction, indeed who must still bring them, who have sensed his mission in the deepest and most joyful way. They are the ones who have the most honest and passionate love for him as Führer and as a man. That is the result of the magic of his personality and the deep mystery of his pure and honest humanity,

It is of this humanity, which those who are nearest to him see most clearly, of which I speak today.

All genuine humanity is characterized by simplicity and clarity in being and in action. It displays itself in the smallest as well as the greatest matters. The simple clarity that is evident in his political nature is also the dominating principle of his entire life. One cannot imagine him putting on a front. His people would not recognize him were he to do so. His daily meals are the simplest, most modest, imaginable. He dines no differently whether with a small group of friends or at a state banquet. At a recent reception for officials of the Winter Relief program and old party member asked him if he could have an autographed copy of the menu as a souvenir. He paused for a moment and then laughed: “That’s fine. The menu stays the same here; anyone is welcome to look it over.”

Adolf Hitler is one of the few state leaders who avoids medals and decorations. He wears only a single high medal that he earned as a simple personal solider displaying the greatest personal bravery. That is proof of modesty, but also of pride. There is no one worthy to decorate him, other then he himself. Any form of ostentation is foreign to him, but when he represents the state and his people, he does so with impressive and appropriate grace. Behind all that he is and does are the words of the great soldier Schlieffen, who wrote: “Be more than you seem!” His industry and determination in reaching his goal far exceed normal human strength. Several days ago I returned to Berlin at 1 a.m. after several hard days and was ready for sleep, but he wanted a report from me. At 2 a.m. he was still alert, still at work all alone in his home. For two hours he listened to a report on the construction of the national highways, a theme that would seem distant from the great international problems with which he had been occupied the entire day from early in the morning to late at night. Before the last Nuremberg rally, I was his guest for a week in Obersalzburg. The light shone from his window each night until 6 or 7 a.m. He was dictating the great speeches he would give a few days later at the rally. His cabinet approves no law that he has not studied to the smallest detail. His military knowledge is comprehensive; he knows the details of each weapon, each machine gun, as well as any specialist. When he gives a speech he knows each detail. His working method is entirely clear. Nothing is further from him than nervousness or hysterical tension. He knows better than anyone else that there are a hundred problems to be solved. He chooses the two or three he finds most central and works on them, undistracted by the remaining ones, for he know that if he solves the great problems, the problems of second or third magnitude will solve themselves.

His approach to problems shows both the determination necessary to deal with essentials and the flexibility essential in the choice of methods. He has principles and beliefs, but he knows how to reach them by careful selection of methods and approaches. He has never changed his basic goals. He does today what he determined to do in 1919. But he has always been flexible in the methods he used to realize his goals. When he was offered the vice chancellorship in August 1932, he rejected the offer. He had the feeling that the time was not yet ripe and that the ground offered to him was too small to stand on. But when he was offered a wider door to power on 30 January 1933, he walked courageously through it. It was not the full responsibility he wanted, but he knew that the ground he know stood upon was sufficient to begin the fight for full power. The know-it-alls understood neither decision. Today they must reluctantly grant that he was superior not only in his tactics, but also in the strategic use of the principles in ways they short-sightedly failed to see.

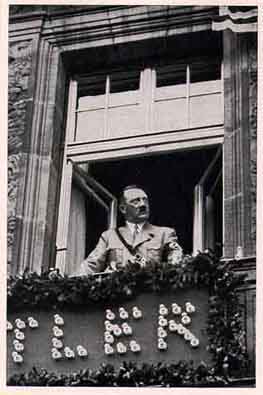

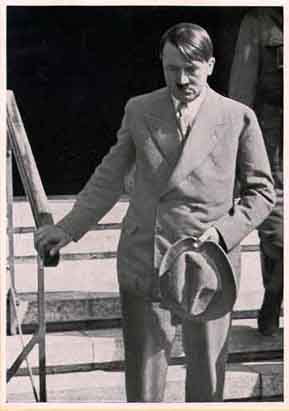

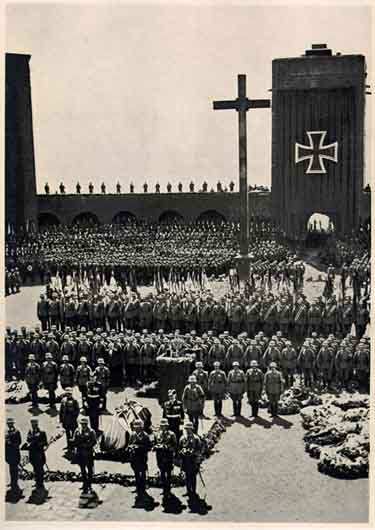

Two pictures last summer vividly showed the Führer in all his aloneness. The first showed him greeting the Wehrmacht just after he was forced to bloodily put down the treason and mutiny of 30 June. His face showed the bitterness of the difficult hours he had experienced. The second photograph was of him leaving the house of the dying marshall and Reich president in Neudeck. His expression shows the shadow of pain and sorrow in the face of pitiless death that in a few hours would tear from him his fatherly friend. With almost prophetic foresight to told us in his innermost circle on New Year’s Eve that 1934 would be a dangerous year, one which would likely see the death of Hindenburg. Now the inevitable had happened. One thing was plain in his granite face: the pain of an entire nation, a pain that would not descend to mere complaining.

The entirely nation not only honors him, it loves him deeply and fervently, for it has the feeling that he belongs to them. He is flesh of its flesh and spirit of its spirit. That shows itself in the smallest aspects of everyday life. It is plain in the camaraderie in the Reich Chancellery between the least SS man and the Führer. When he travels, he sleeps in the same hotel and under the same conditions as everyone else. Is it any wonder that the least of those around him are the most loyal?! They have the instinctive feeling that his is no facade, but rather the result of his inner and obvious spiritual nature.

Several weeks ago, 50 young German girls from abroad, who had completed a year of schooling and were now about to return to their suffering home countries, visited the chancellor, hoping to see him for a moment. He invited them all to dinner. For hours they had to tell him of their modest lives. As they were leaving, they suddenly sang the song “If All Become Untrue,” and tears flowed from their eyes. In the midst of them stood the man who has become the incarnation of eternal Germany, giving them friendly and good-hearted consolation to encourage them on their difficult journey.

He came from the people and remains a part of them. He who negotiated for two 15-hour days at a conference with diplomats of mighty England, who mastered arguments and facts on the great questions of Europe, can speak with complete ease to ordinary people, and can with a comradely “Du” restore the confidence of a fellow war veteran who greets him with a nervous heart after perhaps days of wondering how to greet him and what to say. The weakest approach him with confidence, for they sense that he is their friend and protector. The entire nation loves him because it feels as safe in his arms as a child in the arms of its mother.

This man is a fanatic in his cause. He has sacrificed his personal happiness and private life. He knows nothing other than the work that he does as the truest servant of the Reich.

An artist becomes a statesman, and his historic work reveals his remarkable abilities. He needs no external honors; his greatest honor is the enduring permanence of his labors. But we who have the good fortune to be near him each day receive light from his light and want only to be obedient followers behind his flag. Many times he has told the circle of his oldest fellow fighters and closest friends: “It will be terrible when the first of us dies and there is an empty place here that can no longer be filled.” May a gracious fate ordain that he live the longest, that for many decades the nation will continue under his leadership along the path to new freedom, greatness and power. That is the honest and passionate wish that the entire German nation lays in thankfulness at his feet. Not only we who stand near him, but also the last man in the most distant village, join in saying:

“He is now what he always was, and always will be: Our

Hitler!”

[Page copyright © 1998 by Randall Bytwerk. No unauthorized reproduction. My e-mail address is available on the FAQ page.]

Go to the 1933-1945 Page.

Go to the German Propaganda Archive Home Page.