Background: The Kampfzeit,or “period of struggle”, was the Nazi term for the years 1919-1933 when the Nazi Party was fighting for power. This book is typical of a fairly large amount of Nazi material glorifying those years. The author, Hans Hinkel, was an early member of the Nazi Party who held a senior position in the Propaganda Ministry after 1933. In this book, he builds the myth of the Kampfzeit as a time when a few brave and loyal Nazis fought against overwhelming odds. I translate sections of the book that deal primarily with his activities as a speaker.

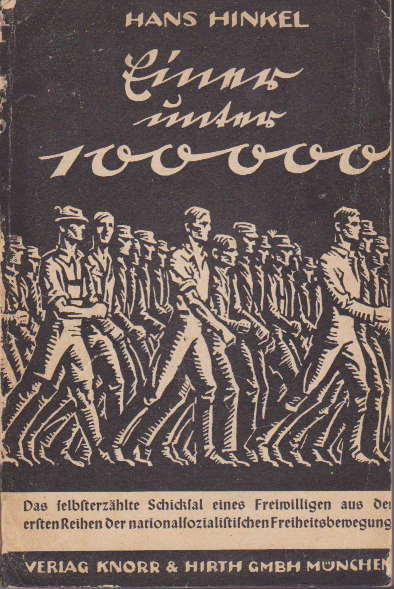

The source: Hans Hinkel, Einer aus Hunderttausand (Munich: Verlag Knorr & Hirth, 1943). The book was originally published in 1937.

The number of party members who in those days traveled through regions of the fatherland, or even through all of Germany, to preach or speak about the Führer’s idea was still small. Those who a few years later were named Reich speakers by the party leadership, but who were already traveling throughout Germany, can tell stories of the tremendous resistance they had to overcome, of the prejudices that they had to fight against for months or even years, of the cloud of lies that the united front of our opponents spread about our Führer and his movement. Faster than lightning, a lie about us spread throughout the country, spread to every attic room where poor people lived by newspapers owned or obedient to the opponent. It took a week of work by us National Socialists to deal with a three-line lie in an opposing newspaper. As soon as one lie was dealt with, a hundred more sprang up. Like a hydra, the opponent’s horror stories about National Socialism and its supporters spread. There was not a speech by the Führer or his associates that was not immediately twisted and tastefully served up to the gullible Michael [a generic term for the average German] at breakfast or dinner. Adolf Hitler had “spat out the communion wafer.” Hermann Göring was smuggling opium or morphine. Robert Ley had “lost a ‘v’” in his name [Ley had been accused of changing his name from Levy to Ley — that is, of concealing Jewish ancestry.]. Pastor Münchmeyer [a prominent early Nazi speaker who had been defrocked as a Protestant minister] was guilty of “moral crimes” in Borkum. We often would have laughed had we not hourly learned the amazing gullibility of millions of German citizens who were trapped in the enemy’s web of lies. The only answer was for everyone to set to work with the people, going everywhere to fight, speak, and educate. Sooner or later the opponent would have to face us and be revealed as a liar to the public.

To summarize these days briefly, I turn to letters that I

wrote then to my friends that told of the great difficulties

we faced. In December 1926 I wrote:

To summarize these days briefly, I turn to letters that I

wrote then to my friends that told of the great difficulties

we faced. In December 1926 I wrote:

Today I worked out the meeting plan with Gauleiter Schultz. Eight days from now on Wednesday, I speak in Homburg, Thursday in Melsungen, Friday in Kassel (a discussion evening), Saturday in Altmorschen, Sunday afternoon in Oder-Ellenbach, Sunday evening in Bisförth. Monday there is an S.A. propaganda march in Kassel, Tuesday in Eschwege, Wednesday in Spangenberg, Thursday in Arossen, Friday in Malsfeld, Saturday in Korbach, and Sunday in Massenhausen. The following Monday is finally free. Tuesday I leave for 2 days in the Marburg area.

That is the pace at which we speakers had to work. Cities and villages alternated in our calendars. It went that way month after month, week after week. Usually only Monday was free of meetings. We fought for each individual. We read today in our reports of those days that “at a large mass meeting” — with 700 persons! — eight new members joined and we gained four new readers for our few party newspapers. In Arossen it was nine and six, in Massenhausen only three, in Marburg seven and eleven, and in Eschwege two new members and three new newspaper readers. In some villages and cities, even a single new man was a success for us. Sooner or later, it was the same in every corner and part of Germany as it was in Gau Hessen-Nassau. Too often we had to try to hold a meeting three, four, or six times in a city before we finally succeeded. Often the first attempt at a meeting was disrupted by force by an opponent a hundred times as strong we were, or made impossible by their ruthless efforts to keep their followers from attending our meetings. We had to keep our nerve and avoid being distracted — the states attorney was always ready to enforce the “Law for the Defense of the Republic”! — and always be ready to make a new attempt. This struggle made us National Socialists tough — tougher than our opponents thought and tougher than any outsider thought possible, or even could understand. We were inwardly steeled and lost the last vestiges of any forgiveness complex we may have had. No mockery and no crude insults could take away our conviction that we National Socialists were, as one of our old guard once said, Germany’s last hope.

Unemployment was particularly severe that winter in Kassel. The city council, its majority loyal to the System, tried to keep the victims of the Dawes Plan [an international agreement on German World War I reparations payments],in check with empty words and the police. The few National Socialists, headed by Roland Freisler [later a notorious Nazi jurist], waged a desperate battle. Just before Christmas of that year, the city council met. The Weimar majority had just voted down emergency Christmas assistance for the unemployed! Thousands and thousands of citizens who had been robbed of their right to work gathered outside the large and lovely city hall, ready to storm the building. Every available policeman was there to guard the Novemberlings [the Nazi term for the leaders of the Weimar system]. Those who a few years before cheered “their” mayor Scheidemann had realized their betrayal. The city was like an upset anthill on that cold winter night. Roland Freisler ran out from the chattering council meeting and went with us to the nearby Friedrich Square where we spoke with the starving masses. We forgot the middle class niceties! We had to stop Moscow from winning over these citizens driven crazy by hunger, making them willing subjects of the insane ideas of Bolshevism...

If the city of Kassel was spared mass plundering and hard bloody fighting, it is thanks to a few hundred S.A. men that stood beside us speakers and demonstrated the national socialism of our movement! — Only a few weeks later, I needed an escort to leave or return to my apartment. Several loyal S.A. men had to be with me all the time, since communist unemployed men, unscrupulously incited against us National Socialists, wanted to attack me now that they knew who I was. Every day I joined the unemployed who demonstrated in the large courtyard of the labor office on Giesberg Street. More than once I had to be met by party members at the Kassel train station to protect me from lurking communist terror troops. It was the same or worse for all of our prominent Kassel party members and S.A. men, just as for the storm troops of our movement who risked their lives every day and every hour in every city and every village of Germany. The enemy naturally was particularly after us speakers. According to the law, we had to be unarmed. We would have been in deep trouble if a body search had found a weapon! A nail file was thought to be a weapon. Later even a party badge, since it had a long needle!

The officials of the System believed that such measures would keep us from making any progress. Their “faith” was our good fortune. The gentlemen miscalculated. [pp. 202-206]

The party office in Wesphalia asks me to come there for eight to ten meetings at least every other month. Those cities that were not red fortresses were entirely in the hands of the Center Party. A bitter battle had begun here and elsewhere in the west. Here one’s full efforts were necessary to win over every single heart. Manual laborers in particular need to hear our thinking. The attempts of our party comrades to hold a National Socialist meeting failed a half dozen times or more. Most meetings were made impossible by the thousand-fold numerical superiority of the opponent, or else broken up before they could finish. Our protective service —every party member in each local group belongs — is still too weak in most areas to stand up against the red avalanche, driven more and more by the communists. One National Socialist against five hundred or even a thousand citizens, that is how it always is there!

In the middle of the month I go to Dortmund. Our meeting is in the red north of the city, at the “Fredenbaum.” Two thirds of those present may be Marxists. This day in November, nine years after the stock exchange revolt [The claim is that the 1918 German revolution was directed by “stock exchange Jews”] and four years after Adolf Hitler’s deed [the 1923 “Beer Hall Putsch”] — allows me to speak from my own experience. I give it a try, describing my own experiences in 1918 and 1923. Based on that, I predict a Marxist betrayal of the German population. The interruptions grow louder, and in one corner of the room there has already been a fight for several minutes, but our comrades quickly succeeded in throwing the troublemakers out. During the discussion period, five Marxists are to speak — two communists, two Social Democrats and a so-called Syndicalist. After a flood of phrases from a Social Democrat, a communist attacks us in the most perfidious way. He says Adolf Hitler is a “fool” and the “leader of the organization that murders workers”! That’s enough! Ten minutes later, and after a hard fight, our comrades succeed in throwing the far more numerous communists out of the hall. About half the audience is left, and I come to my conclusion faster than expected. After I had spoken about twenty minutes, a worker jumped up on a table and called upon the “comrades” to leave the meeting of the “Fascist band.” Several dozen start singing the “Internationale” and we have no choice but to overpower the growling of the comrades with “Deutschland, Deutschland über alles.” Another several hundred leave the hall. The singing quieted down and peace was slowly restored. I spoke to several hundred people at the end, all that were left of the more than a thousand who were there to start.

We sat afterwards for a few hours in the back room of a small party office. The local group leader, old Kämpen König, told me that the meeting gained seven new members and perhaps a half dozen subscribers for the Völkischer Beobachter [the Nazi Party national newspaper]. König, a worker from the Hoelsch iron and steel works, was very satisfied. The S.A. leader Franz Bauer, an old veteran, and his comrade Arthur Heimmich thought it could have been worse, since we were able to end the meeting as planned. Neither had believed that their “Sturm 68” could hold the place.

I learn this evening that as early as October 1920 a man raised Adolf Hitler’s flag in Dortmund: Wilhelm Ohnesorge, a Nazi postal official. I had met Ohnesorge the previous week in Hagen, where he was now working. He founded the first party outpost here in Dortmund at a time when only a few places in the entire Reich had heard of Adolf Hitler. A loyal comrade, the old Free Corps fighter Wilhelm Kolm, was at his side. Kolm along with a troop of uplanders from Bavaria had occupied the central post office in Dortmund a few months previous to keep it out of the hands of the boys from Moscow. The two men met then and formed a life-long fighting comradeship. Kolm put his uplanders at Ohnesorge’s disposal as the first small protective force for the local group Ohnesorge had founded. And since Kolm had been made homeless by the November Republic, postal official Ohnesorge put him up in his home the next night. In the columns of the miserable newspaper the Dortmunder Generalzeiger, that was a declaration of war by a straggler against an enemy a hundred thousand times as numerous. König told me that one of the first comrades who spoke during the party’s early years was Hermann Esser, whose speaking ability helped firm up small National Socialist outposts in the middle of these red fortresses. Over the years, in tireless labor and constant battle that spared no comrade from the worst and most foul, postal official Ohnesorge won man after man. I learned during my visit in Hagen what Wilhelm Ohnesorge meant for the numerically tiny group of National Socialists. I could compare this man only with my fatherly friend in Seidboldsdorf in Lower Bavaria [a friend discussed earlier in the book]: they were the kind of men each of us wished our fathers had been! [pp. 214-217]

For years now we speakers have been traveling through every Gauin Germany. I speak primarily in Saxony, Brandenburg, Hessen-Nassau, and in the West. We see that even red Saxony is streaming more and more to National Socialism. The meetings are difficult, but always successful.

For weeks I travel through the Erzgebirge, just as I did some months before. Things were happening in Annaberg. The meeting there was a great success. Splendid chaps work for the movement in this city. When I speak in the tiny and tiniest villages of the Erzgebirge I sense not only the dreadful poverty of the inhabitants, but also the terrible fatalism with which they bear their lot. Those families who do their work at home are particularly miserable. If these people do not learn to believe in National Socialism, they will all fall into Bolshevism. I spend a while in Neuhausen in the Erzgebirge and have time to study the situation. Pay in the toy-making industry is shameful; the firms are themselves at the end of their resources because exports have dried up. Everyone is fighting with everyone else.

A few weeks later we are delighted to get a lovely package of hand-carved toys just before Christmas. We know the value of this loving gift.

At many meetings, the Marxists bring bloody terror. Our brave S.A. men are tremendous. It was particularly grim in Chemnitz. Nearly half those at a big meeting were Red Front Fighters. One almost cried to see the innocent young lads, and men among them! We have to win these betrayed citizens back. They are the target, not the middle class, most of whom do not want to fight and the rest of whom accept things as they are.

I spend a few days in Lehnitz working out a new kind of propaganda. I want to test it out on my next speaking tour in the Lower Rhine area, party comrade Florian’s Gau. I do not know why I started doing it, but for several years I have been collecting pictures from newspapers and illustrated magazines of every party orientation from the Red Star to the Woche. I have pictures of all the leading System politicians, court reports, pictures of society. I had the feeling that they might be useful some day. While reading them as part of my editorial duties, I often wondered why the lords of the System press were so stupid and so confident as to photograph their party’s saints in the worst situations and then present them to the starving public. The newspaper Jews perhaps wanted to prepare the way for communism, even if they were working for “nationalist” papers. That gave them particularly good opportunities!

A school friend, now a starving engineer in Berlin, told me about a projection device that enlarged everything. I had to have it, even if it cost a lot of money. No sooner said than done. The ever-practical Hansl Hornauer made me a huge packing crate, since the big thing and all its parts had to be carted from meeting to meeting. I pasted the newspaper and magazine photographs to cardboard and added amusing or serious captions. I made sure to include the source of each picture. I also prepared title sheets with text on a white background, particularly figures from the Unpeace Treaty of Versailles or the Young Plan [an agreement on German WWI reparations payments] or the emergency decrees of the System government. I arranged them all in the proper order and was ready for action. The big crate came along in the baggage car. An acquaintance was kind enough to bring us to the North Station with his car. As we hauled it through the Anhalter Station, Hansl Hornauer commented: “Well, the lads in Düsseldorf will be delighted to see this!”

The “premiere” was in a large hall. It was all so new that the crowd was interested in it for that reason alone. Now there was something to see. I did not need to say much. After a brief introduction, I got going. “Pictures without words,” I said. Then they saw Berlin from every angle: miserable housing in Wedding and the East, Mrs. Representative X in the latest society outfit, the leaders of this “Free Republic,” pictures of our “banned” S.A., Jews in the black-red-gold party [the Nationalists], priests as parliamentarians, “colleagues” in the Reichstag restaurant, Isidor [the mocking Nazi name for Bernhard Weiss, the Jewish vice chief of police in Berlin] in a riding outfit, Soviet Jews, this and that, and much, much more, all mixed in with the figures from Versailles and Dawes. It was effective. The pictures from the November Revolt and Russia were particularly effective, as were the pictures of the past and of the “Dessau” Bauhaus buildings. I was pleased that Jewish film pictures were greeted with laughter. In the conclusion, I spoke strongly. I stressed that all the pictures came from newspapers and magazines that were our enemies, even the caricatures of Comrade Scheidmann with and without his goatee, the pictures of Bernhard Weiss dancing with film star Y or Reichsminister the Jew Rudolf Hilferding M.D. in conversation with Reichsbanner general [the Reichsbanner was the socialist paramilitary force] Hörsing. All these were taken not by a National Socialist, but rather by a Jew for the society pages of the Berliner Tageblatt. And the signatures at the bottom of the “Treaty” of Versailles were those of Dr. Bell and Herman Müller...

My new propaganda method worked particularly well in smaller towns. Every photo from a so-called big-city newspaper hit the mark. The descriptions of the latest fashions in the Jewish papers, which praised “socialism” on their other pages and railed against the bourgeoisie and capitalism, found excited readers. They saw the original material on the screen before them. None of the opponents present could doubt that.

I traveled though many districts with my crate for months. Then it was taken from me by government order. “Slandering the Republic!” — Insulting the representatives of the present state!” — “Incitement to violence!” —

I could no longer use the crate if I did not want to face constant fines of a thousand marks. There was a fine for noncompliance of RM. 20 — or 10 — or two days in jail! —

So I got along without the crate. Meeting followed meeting. We propagandists of Adolf Hitler traveled throughout Germany. To the smallest village. —

For how long? When would this hard battle end? When would more Germans wake up? When would hundreds of thousands finally be ready to march into battle behind the banner of National Socialism?! —

None of us thinks about the “when.” Forward! — Only forward! Each heart won over is a victory! The day will come...! — [pp. 259-262]

[Page copyright © 2001 by Randall Bytwerk. No unauthorzed reproduction. My e-mail address is available on the FAQ page.]

Go to the German Propaganda Home Page.